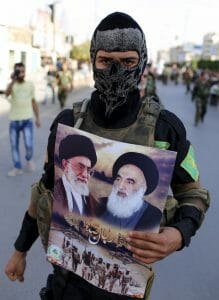

„Last Monday, Nouri Al Maliki, Iraq’s former prime minister, said the forces taking part in the operations in Nineveh – dubbed by Baghdad ‚We are coming, Nineveh‘ – will march on to Raqqa, Aleppo and Yemen. He added that the fight will continue everywhere against those who apostatised from Islam, a phrase reminiscent of ISIL’s takfiri talk. He spoke at a conference titled Islamic Awakening, an annual event in reference to the 2011 Arab uprisings, which was first organised by Iran in 2012. Ahmad Al Assadi, a spokesman of the Hashd Al Shaabi, also claimed that the militia organisation will move on to fight ISIL in Syria after Mosul is retaken.

The statements came days before the Hashd Al Shaabi formally began its operations against ISIL west of Mosul. As stipulated by the operation’s strategy, the pro-government militias will not be allowed to fight inside Mosul but will provide rearguard support. The militias will spearhead the attack to retake Tal Afar, one of ISIL’s strongholds north- west of Mosul, and disrupt the Raqqa-Mosul supply route inside Iraq. The situation around Mosul is still positive. But the sectarian statements over the past week as the Iranian-backed militias join the battle provide a window to what could go wrong during this iconic battle.

If ISIL bides its time inside and outside the city, there could be a change in strategy, including the entry of Shia militias to the battlefield in the city. The sectarian and transnational statements about Mosul and Aleppo make such an outcome conceivable. Qays Al Khazaali, the leader of Asaib Ahl Al Haqq, one of the groups participating in the operation, said over the weekend that the Hashd Al Shaabi are the avengers of Hussain, the grandson of Prophet Mohammed killed by the Ummayids, and that ‚it is with this doctrine that we will fight them in Mosul‘. (…) These remarks, combined with reported human rights violations, are troubling. ISIL might not be the only force that seeks to disrupt the current strategy that supposedly keeps sectarian militias outside the city. Like ISIL, these groups might also seek to undermine the plan as it stands now.

As these groups intensify sectarian threats, some people in Syria and in the region started to wonder whether the defeat of ISIL in Iraq will mean many of these militias will indeed flood into Syria. The infrastructure for their operations in Aleppo and elsewhere is already in place. More fighters from these groups, if clashes in Iraq stop, will have immense implications for Syria. This prompted people, such as Syrian journalist Moussa Al Omar, to ask whether Syrians now view ISIL as a bulwark against the hordes of sectarian Iraqi militias flowing into Syria.

Two weeks into the battle to liberate Mosul, these underlying troubles should worry the US-led coalition. ISIL clearly wants Mosul to be its Dabiq, the supposed apocalyptic site for a final epic battle but which it lost to the Syrian rebels without much of a fight just before the Nineveh operation began. Mosul might not be the apocalyptic alternative, but it could provide ISIL with the defining polarisation that it seeks.“